The Weight of Infinite Desire

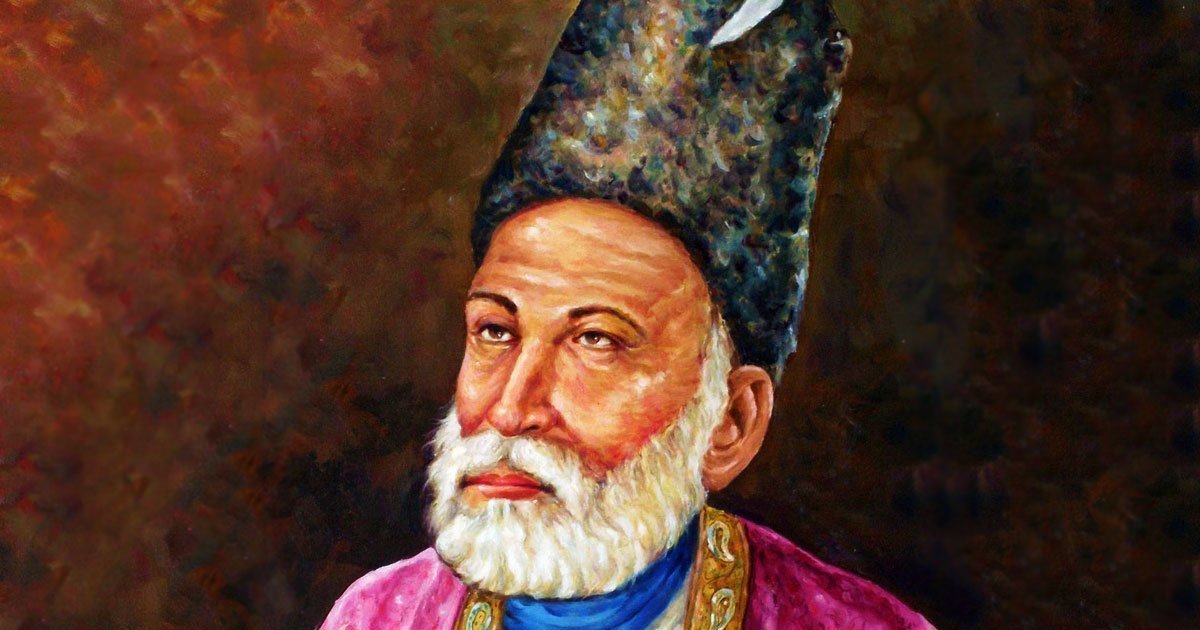

There’s a moment when you realize that fulfillment isn’t the opposite of longing. It’s something else entirely. Mirza Ghalib understood this in a way that pierces through centuries. His opening couplet of this ghazal strikes at something we all recognize but rarely admit: hazaron khwahishen aisi ki har khwahish pe dam nikle. A thousand yearnings, each one costing you your breath.

This isn’t poetry about wanting things. It’s about the texture of desire itself, how it wears on the soul. When Ghalib speaks of thousands of wishes where each one demands your life, he’s describing something we live with every day but struggle to name.

Line by Line: The Original and Its Meaning

Let’s walk through this masterpiece slowly. The language here is Persian-inflected Urdu, layered with meaning that a single translation can never fully capture. But we can try.

The Opening Couplet (Matla)

hazāroñ ḳhvāhisheñ aisī ki har ḳhvāhish pe dam nikle

Translation: I have a thousand yearnings, each one afflicts me so.

Notice the word dam here. It means breath, life force, spirit. Every single desire exacts a price in your very essence. This isn’t metaphorical in the way we use that word casually. For Ghalib, this is literal spiritual currency.

bahut nikle mire armān lekin phir bhī kam nikle

Translation: Many were fulfilled for sure, not enough although.

Here’s the paradox that makes this ghazal unforgettable. Even when desires are satisfied, even when many wishes come true, there remains this persistent insufficiency. The human heart knows no satiation. This echoes what you’ll find in deeper spiritual texts, where the soul’s hunger cannot be filled by material fulfillment alone.

The Second Couplet (Doosra Shair)

Dare kyuuñ merā qātil kyā rahegā us kī gardan par

Translation: Why is my murderer afraid would she have to account.

The beloved here is called qātil, the murderer. In Urdu love poetry, the beloved kills the lover through indifference. But notice the question: why should she fear? Why should she worry about consequences?

vo ḳhuuñ jo chashm-e-tar se umr bhar yuuñ dam-ba-dam nikle

Translation: For blood that ceaselessly, from these eyes does flow.

The tears are described as blood flowing from tearful eyes, lifetime after lifetime, moment after moment. This is the imagery of spiritual martyrdom. The lover doesn’t resist. They’re willing to bleed endlessly.

The Third Couplet

nikalnā ḳhuld se aadam kā sunte aa.e haiñ lekin

Translation: From Eden, of Adam’s exile, I am familiar, though.

Now Ghalib invokes a larger mythology. Adam’s expulsion from paradise is everyone’s expulsion. We’re all exiles from something perfect.

bahut be-ābrū ho kar tere kūche se ham nikle

Translation: Greatly humiliated from your street did I have to go.

But the shame of leaving the beloved’s street is deeper than the shame of leaving Eden. The lover walks away dishonored, stripped of dignity. This is what longing does to us.

On Illusions and Truth

bharam khul jaa.e zālim tere qāmat kī darāzī kā

Translation: O cruel one, illusions of your stature all will know.

agar is turra-e-pur-pech-o-ḳham kā pech-o-ḳham nikle

Translation: If those devious curls of yours could straighten arow.

There’s bitter humor here. If the beloved’s elaborate curls could be straightened, all the delusions about their grandeur would dissolve. The physical beauty is a trap, ornate and twisted like the curls themselves.

The Madness of Love’s Service

magar likhvā.e koī us ko ḳhat to ham se likhvā.e

Translation: If someone wants to write to her, on me this task bestow.

huī sub.h aur ghar se kaan par rakh kar qalam nikle

Translation: Since morning I am roaming with a pen upon my brow.

The lover is so devoted they carry a pen on their forehead, ready to write letters to the beloved. They’ve become a vessel for service. This speaks to something deeper than romantic love, something closer to spiritual devotion where the self dissolves into purpose.

When Past Returns

huī is daur meñ mansūb mujh se bāda-āshāmī

Translation: The rites of drinking at this time with me associate.

phir aayā vo zamāna jo jahāñ meñ jām-e-jam nikle

Translation: Days are here now again when Jamshed’s wine does flow.

Jamshed’s cup is a mythological reference to the legendary king’s magical wine cup. The past returns, and with it, the old intoxication. The lover is caught in cycles of desire and memory.

The Wound of Sympathy

huī jin se tavaqqo’ ḳhastagī kī daad paane kī

Translation: For my injuries, from those that, praise I did expect.

vo ham se bhī ziyāda ḳhasta-e-teġh-e-sitam nikle

Translation: They too turned out to be wounded, actually more so.

Those the lover hoped would sympathize with their wounds turned out to be more wounded themselves. Compassion fails because everyone is suffering. We’re all too injured to help each other.

Love’s Paradox

mohabbat meñ nahīñ hai farq jiine aur marne kā

Translation: In love there is no difference ‘tween life and death do know.

usī ko dekh kar jiite haiñ jis kāfir pe dam nikle

Translation: The very one for whom I die, life too does bestow.

This is the paradox that defines spiritual transformation through devotion. Living and dying become the same thing. The beloved is called a kafir (disbeliever), yet by dying for them, the lover finds life. This mirrors the spiritual teaching of dying before death.

The Final Couplet (Makhta)

kahāñ mai-ḳhāne kā darvāza ‘ġhālib’ aur kahāñ vaa.iz

Translation: Wherefrom the saintly priest, and where the tavern’s door.

par itnā jānte haiñ kal vo jaatā thā ki ham nikle

Translation: But as I entered he was leaving, this much I do know.

Here Ghalib signs his name, as is custom in the ghazal form. There’s a final twist: the distinction between the sacred (the preacher) and the profane (the tavern) collapses. When the preacher leaves and Ghalib enters, or vice versa, what does it matter? Both are paths of devotion. Both lead to dissolution of the self. This playfulness masks something profound: the realized soul recognizes that all paths converge.

Why This Ghazal Still Breaks Us

What makes this particular ghazal transcendent is its refusal to resolve. There’s no comfort here, no redemption arc. Just the naked acknowledgment that existence is desire, that desire devours us, and that we accept this willingly. The beloved doesn’t change. Our wounds don’t heal. The past returns again and again.

And somehow, in that acceptance, there’s a strange peace. Not the peace of getting what you want. But the peace of understanding that the wanting itself is the point. The breath spent on yearning is the most alive you’ll ever feel.

This connects to what longing creates in absence. Ghalib knew that fulfillment flattens the soul. It’s the reaching, the ache, the thousand unfulfilled wishes that keep us vivid, sharp, and real.

Reading This Poem Today

We live in an age obsessed with getting what we want. Productivity apps, manifestation techniques, life hacks designed to remove friction from desire. Ghalib would find this amusing and sad. He understood that the friction is the point. The resistance of the world against our yearning is what gives us shape.

When you read this ghazal now, you’re not just encountering poetry. You’re encountering a voice that understood the soul’s true condition. Someone who lived through empires’ fall and personal devastation and still found beauty in the articulation of that pain.

That’s the real power of Ghalib. Not that he offers answers. But that he validates the question itself. He makes suffering feel less like a mistake and more like a vocation.